🗺️ How an AI plans code changes across an entire GitHub Repository

William Zeng - October 9th, 2023

GPT4 can generate unit tests, refactor a function, and add comments/docstrings to your code. You can even use GPT4 with a 32k context window to write an entire app from scratch.

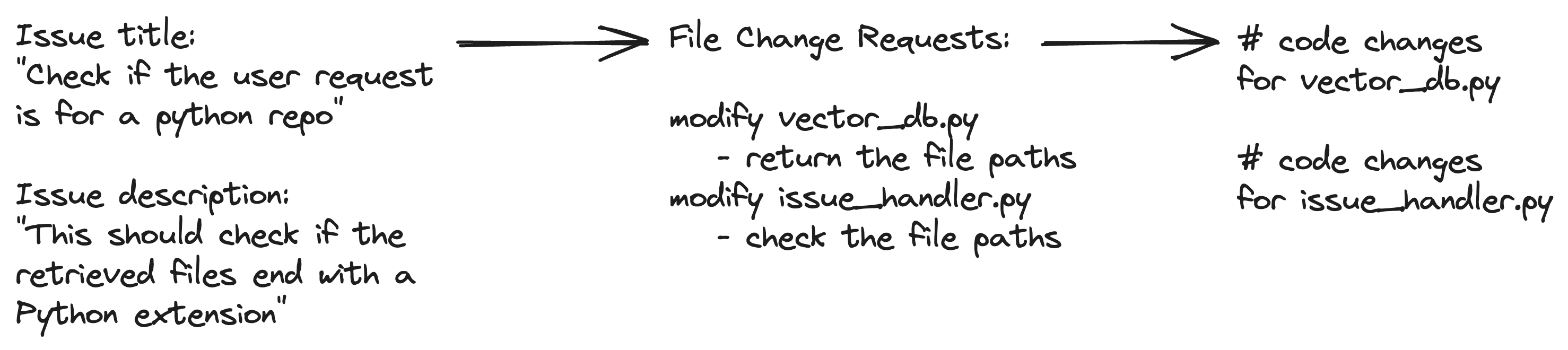

However, to get it to plan code changes at the repository level, such as while solving Jira tickets, we need to do a lot more work. We need to turn the user input from an issue title and description into a set of instructions, and then translate those to code changes. It should look like this:

- Turn the issue title and description to pairs of files and file-level instructions in natural language.

- Turn the file-level instructions from natural language to code changes.

This must include a powerful search engine, but search is not sufficient. By only relying on RAG (Retrieval-Augmented-Generation) we need a lot of luck to get the files we need.

Lexical search and context pruning

We've tried a lot of strategies to manipulate and improve the input context. We encountered an interesting issue everytime we added additional inputs. This will hurt our performance in the short term because of how GPT4 currently degrades in performance (both planning, coding, and instruction following) after ~20k tokens.

This is a prevalent effect known as lost-in-the-middle (LIM) where LLMs only focus on the context at the beginning and end of the prompt. Thus, when we try to add more context, GPT4 will also ignore a lot of it.

1. Prune the Input Context(repository tree and files)

One of the input contexts we tried was the repository tree. We previously only expanded directories containing files that were fetched the hybrid search index, but this is not nearly enough.

<repo_tree>

.github/...

.gitignore

sweep.yaml

sweepai/

sweepai/utils/

__init__.py

buttons.py

hash.py

utils.py

tests/

__init__.py

tests/archive/

additional_modify_prompt.txt

api.ipynb

async_playwrite.py

context.xml

... # ~130 more files

</repo_tree>We pruned the context by having GPT4 name what it wants to remove (say some snippets or paths/directories in the repo) that we clearly don’t need. We started by fetching everything, and only have GPT4 name what it wants to remove.

We end up with a huge list of everything that’s irrelevant, and we hope GPT4 doesn’t name and remove something that’s needed. The entire pipeline would fail when GPT4 pruned something we needed, or forgot to prune useless files.

<paths_to_keep>

* sweepai/api.py

* sweepai/utils/buttons.py

</paths_to_keep>

<directories_to_expand>

* sweepai

* tests

</directories_to_expand>A more reliable way would be to gradually iterate until we hit a happy state. In the above, we can use GPT4 as a context optimizer. If it sees the state of the repo and decides no changes are needed, i.e. keep everything shown and don't add anything new, we’re at a local maxima.

It seems that the model's decision making quality is highest at the 10-15k context window. So we don’t want to make decisions at 20k. Rather we’d make the decision at 10k to both prune and expand the current context, exploring more files and directories, and removing unexplored ones.

This allows us to stay within our context bound while still iterating towards that local maxima we mentioned before.

2. Lexical search for code

Something else that allows us to start at favorable initial conditions in addition to vector search was lexical search. I looked around and tried to find a nice python library for computing TF-IDF, and I landed on whoosh (opens in a new tab). This library is unmaintained and unfortunately caused several deadlocks when we ran this in production with multiple threads trying to access the same cache, even if we set this to cache in memory instead of disk.

So I hit it with the code interpreter hammer: "Write a simple class that implements TF-IDF in memory". We used a python dictionary, calculated document frequencies, and computed TF-IDF on the fly.

Code interpreters's tf-idf implementation. (opens in a new tab) Now we have whoosh at home.

It’s definitely not as performant and we lost a bunch of utilities. But we don’t segfault and we can always optimize later so we need to choose our battles here.

N-grams (another historical trick) also helps here. TF-IDF(the backbone of most lexical search engines) leverages the inverse frequency of a term to boost the ranking. An N-gram captures patterns like vector_db.search or logger.error("), giving us more context than just single tokens.

We also tokenized the code (opens in a new tab) on pascal-case, camel-case, and snake-case. This means that ChatGPT, chat_gpt, and chatGPT all become chat and gpt. This also allows us to heavily match any code that is copied verbatim as well as class definitions and instantiations.

For example, a title like "Refactor the ChatGPT.chat method to use the new API" can match chat, gpt, chat_gpt.chat and class ChatGPT. This works great for code when combined with vector search, which we discussed here: https://docs.sweep.dev/blogs/search-infra (opens in a new tab).

Python AST graph-based planning

I asked ChatGPT for a good code visualization library but all of them were for Python 2. So again I wrote my own using code interpreter. This is the library: https://github.com/sweepai/sweep/blob/main/sweepai/utils/graph.py (opens in a new tab)

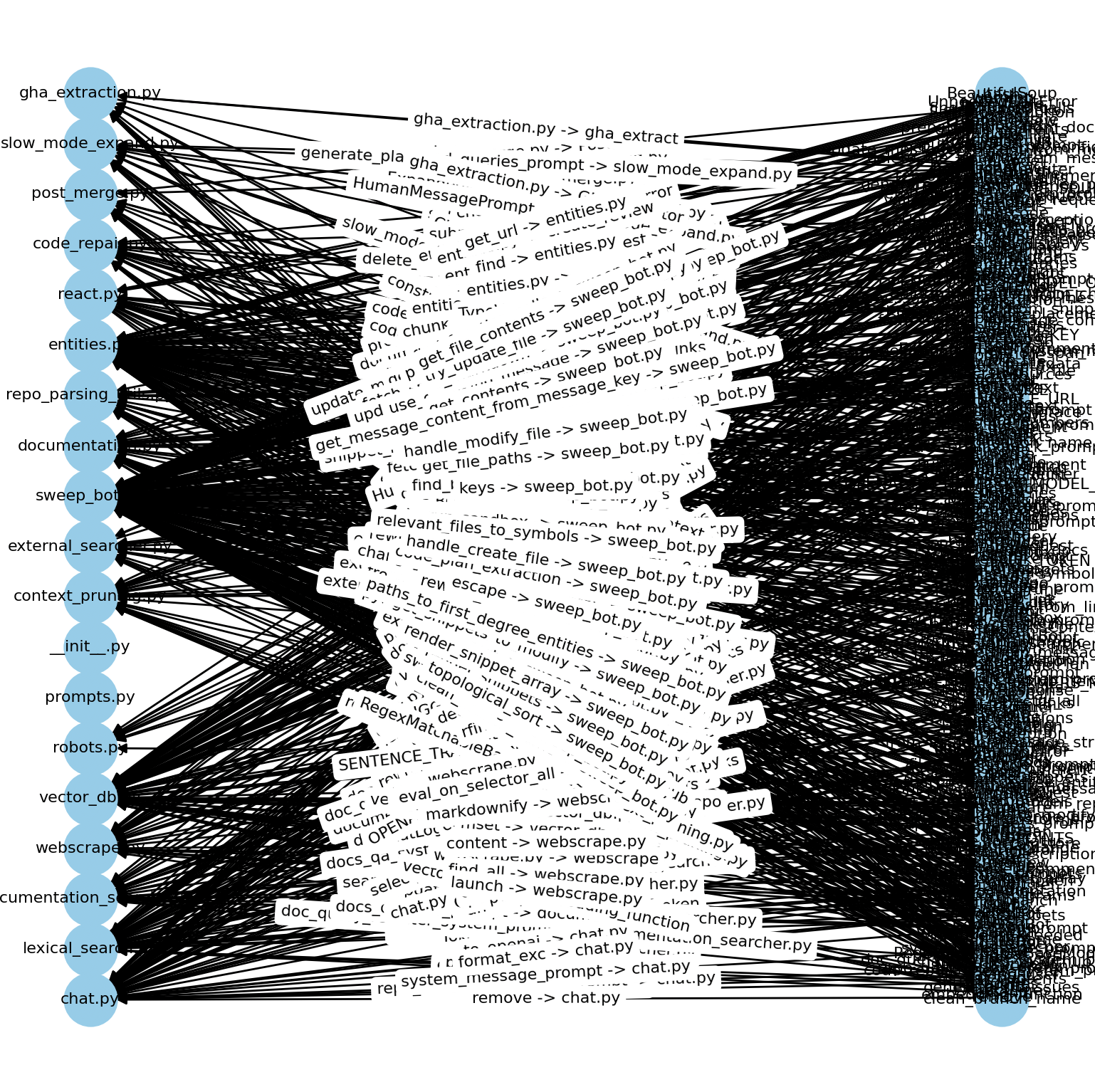

Here’s what it initially generated for sweep/sweepai/core.

This is a bipartite graph of files on the left to entities on the right. Note how dense the graph is, and how some files don’t even have inbound or outbound nodes.

Traversing this graph would have nearly perfect recall for planning, as every function that might be even remotely relevant will be retrieved. But the precision is really bad. The solution to low quality precision is to evaluate each walk (original file, entity, and new file) with an LLM, but this won't work if the graph is terribly noisy.

How do we construct a less noisy graph?

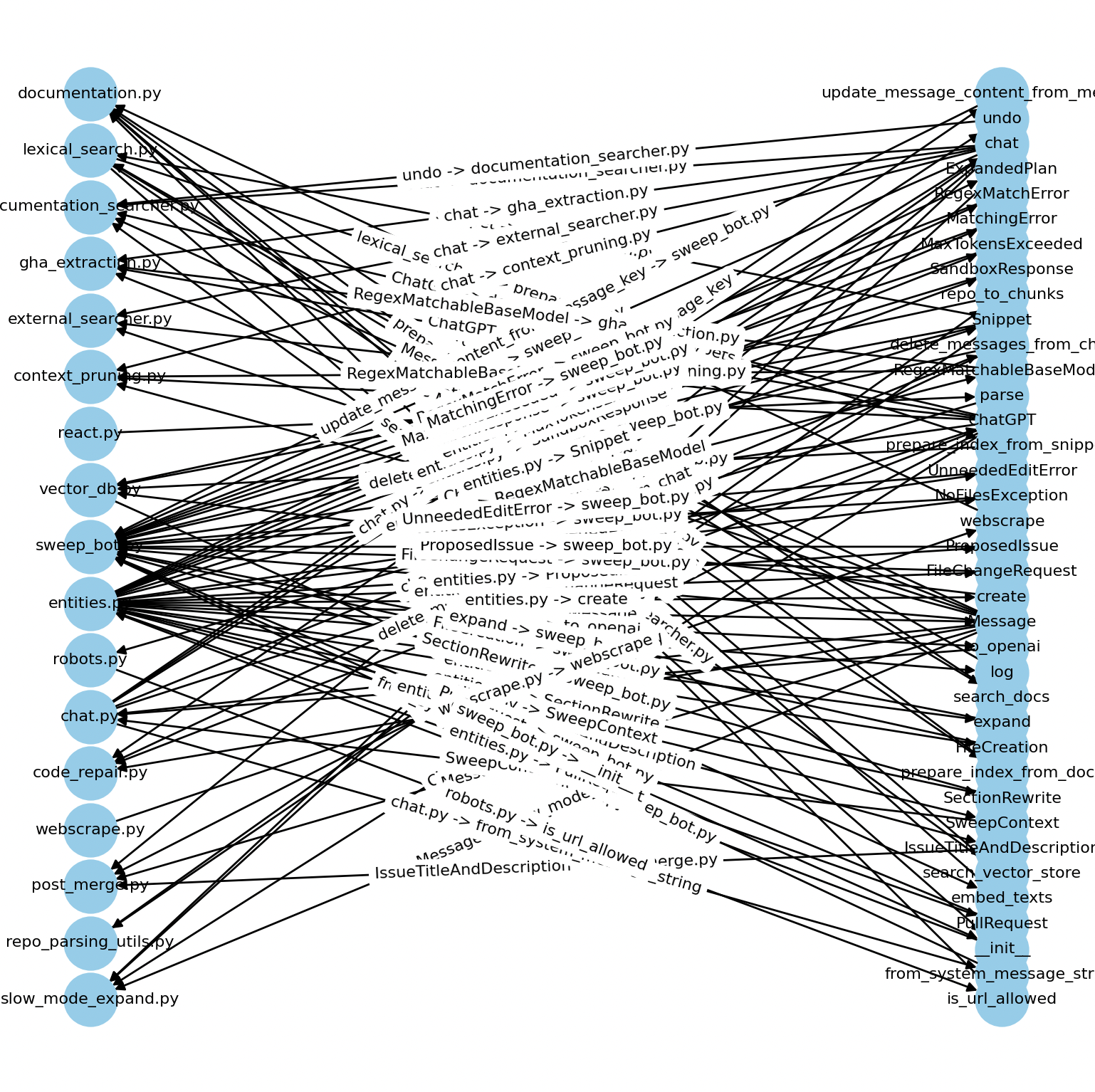

We can remove any entities with in-degree zero. This means that they are not instantiated in a file (either an external dependency import openai or a native dependency say import math). This graph represents any user-specified classes or methods. We dropped the number of edges from 680 → 102. Much better!

So we tried a bunch of stuff and have this nice graph. We can now plan in AST space instead of in file space. We didn’t end up implementing this all the way though, look out for the future.

Why Sweep works with long files

We get huge benefits from this graph of entities. The reason is that in our codebase, we have files that are 1.5k lines long. 2-3 of these will max out the context window of ChatGPT.

So we want to plan in AST space because dropping any of these files into the plan will immediately fill up the entire context window. Even if the file doesn’t blow it up it’s going to destroy performance. Now imagine if we want to orchestrate a change across multiple files that are all >1k lines long.

It’s a fun problem to manage all of these. We do have a saving grace though, which is that code doesn't usually have truly huge unbreakable functions, say:

def print_1000x(text):

print(text)

print(text)

... # 998 more print statements^ this is hard to chunk! usually we'll have something more reasonable like:

def print_10x(text):

print(text)

print(text)

... # 8 more print statements

def print_100x(text):

print_10x(text)

print_10x(text)

... # 8 more print statements

def print_1000x(text):

print_100x(text)

print_100x(text)

... # 8 more print statementsCode is typically separable by class methods or sub functions which are 150-200 lines long, and we only have to fit the functions and a bit more in memory. For example, we might want the class method definition and a sample call to the class.

We used the CST of python to extract all spans that define or mention a certain class, function, or class method AKA entity (we can just check if entity in span). This is not as accurate as static analysis tools like LSPs and type-checkers, but it's a 99% solution. After getting this we can prune each file to only what’s needed to make the code change to it. But how do we get the entities?

We can use the above graph with the initial searched files as the root nodes.

Now we have an initial node set, and we can expand this out by one degree. We clearly can’t fit all of it’s degree 2 neighbors in context, but the extracted entities can fit in context. Ideally the ones that lie within the extracted snippets will be mentioned, and we can prune a set that is guaranteed to have perfect recall.

Set with high recall and low precision -> an intelligent LLM workflow -> Set with high recall and high precision

The LLM is really good at finding the items that are truly relevant, and we need to have high recall and precision. Now we have all of this relevant context, and instructions to be passed to the execution (diff generation and validation).

Example (all of the entities from on_ticket.py):

EmptyRepository, FileChangeRequest, MaxTokensExceeded, NoFilesException, ProposedIssue, SandboxResponse, SweepContext, create defined in sweepai/core/entities.py

SweepBot, get_files_to_change, validate_file_change_requests, generate_pull_request, generate_subissues defined in sweepai/core/sweep_bot.py

ClonedRepo, get_github_client, get_num_files_from_repo, get_commit_history, delete defined in sweepai/utils/github_utils.py

create_config_pr, create_pr_changes, safe_delete_sweep_branch defined in sweepai/handlers/create_pr.py

ChatLogger, add_successful_ticket, use_faster_model defined in sweepai/utils/chat_logger.py

ChatLogger, add_successful_ticket, use_faster_model defined in sweepai/sandbox/src/chat_logger.py

SweepConfig, get_documentation_dict, get_config defined in sweepai/config/client.py

remove_all_not_included, expand_directory defined in sweepai/utils/tree_utils.py

ExternalSearcher, extract_summaries defined in sweepai/core/external_searcher.py

HumanMessagePrompt, get_file_paths defined in sweepai/utils/prompt_constructor.py

ContextPruning, prune_context defined in sweepai/core/context_pruning.py

from_system_message_content defined in sweepai/core/chat.py

extract_relevant_docs defined in sweepai/core/documentation_searcher.py

create_action_buttons defined in sweepai/utils/buttons.py

search_snippets defined in sweepai/utils/search_utils.py

run_sandbox defined in tests/archive/test_modal_sandbox.py

on_comment defined in sweepai/handlers/on_comment.py

review_pr defined in sweepai/handlers/on_review.py

print defined in logn/logn.py

count defined in sweepai/utils/utils.py

on_ticket used in sweepai/api.pyNow that we're able to identify a file and entity, we need to make the correct change. Even if we point GPT4 to a function call, this is still unclear.

For example, if we ask GPT$ to add a parameter to a function (without context), is it an input or output parameter?

def foo(new_param): or def foo(): -> new_param?

foo(new_param) or new_param = foo()?

We need to figure out a way to make sure a changed function signature is passed down to the future modification steps.

Passing context through the change sequence

The trick we used was to pass down the diffs every time we make edits. This is incredibly useful in any scenario where we want to make sure a changed signature func(a, b) → func(a, b, c) has its usages modified.

For example, we originally used for disambiguating between chunks of a large file. Say we have a 1.5k line chunked into 3 sections (0-500, 500-1000, and 1000-1500).

This happened when I wanted Sweep to:

- log whether the issue was a python issue

- fire a telemetry event

- and pass it to the agent (SweepBot)

The telemetry logic was defined at line 400 and SweepBot is defined in line 600. So it’s reasonable to modify it between either of these lines (400-600). In the first chunk, Sweep may or may not actually modify the code. Therefore in the second pass, Sweep is uncertain whether the change should be made (because of the inherent ambiguity mentioned above).

Passing down diffs allows Sweep to know that the change was made, so that at chunk 1 it can modify it, and in this case chunk 2 should see the diff, or alternatively Sweep can skip it in chunk 1 and chunk 2 should see no diffs.

Planning across multiple files

Back from our tangent on long files. Now that we can handle one change in one gigantic file, we have to do this with two files.

Say we have on_ticket using sweep_bot, and on_ticket was modified first. We want to add the is_python_issue to sweep_bot.get_files_to_change. A reasonable way is to set files_to_change, is_python_issue = sweep_bot.get_files_to_change() right?

No it’s not. We want to have it as an argument files_to_change = sweep_bot.get_files_to_change(is_python_issue), but given that GPT4 can’t even read the files at once, it’s not going to properly handle this. The nice thing is that we can topologically sort based on the imports in python.

Python fortunately doesn’t allow a cyclic import graph (a imports b and b imports a), so we can enforce an ordering of sweep_bot.py → on_ticket.py, and on_ticket sees that sweep_bot expects get_files_to_change to take in is_python_issue as an argument.

Finally, after spending 2 days on this, Sweep was able to handle a 15 minute change. https://github.com/sweepai/sweep/pull/1904/files (opens in a new tab) 😀

Conclusion

AI-powered code change planning is still in its infancy stages and we're convinced we only found the tip of the iceberg. However, it seems like the tip is enough to extract value out of it, such as writing small to medium sized refactors.

We're excited to see what the future holds for code planning and to hear your thoughts on it. If you have ideas, feel free to share them in our community (opens in a new tab).